By Katie Kerwin McCrimmon

KEYSTONE Best known for beating brilliant humans at Jeopardy, Watson, the super computer, soon may be coming to a hospital or insurance company near you.

But dont call him (or her) Dr. Watson. The more appropriate reference may be to Sherlock Holmes my dear Watson, the indispensable right-hand man or woman as Lucy Liu now portrays Dr. Joan Watson in the re-imagined TV show, Elementary.

IBMs Watson is actually named to honor the companys founder, Thomas J. Watson. But as Watsons creators dream up future roles for their intelligent machine medical sleuth, patient watchdog and reading buddy to humans may be a handful of them IBM is now trying to tap the silicon genius remarkable ability to digest information in nanoseconds for a variety of health care applications.

Dr. Martin Kohn, an emergency physician for 30 years who is now IBMs chief medical scientist for care delivery systems, came here to the Colorado Health Symposium this week to share the latest concepts with health policy experts from Colorado and the U.S. at the conference sponsored by the Colorado Health Foundation.

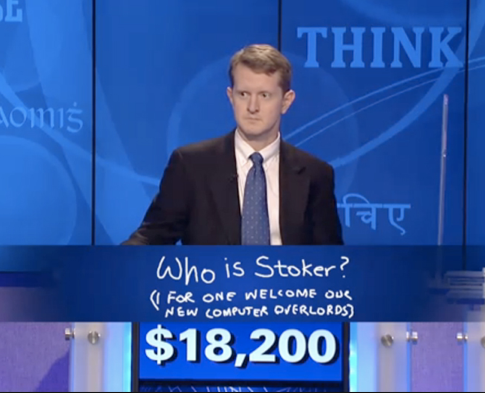

When Watson prevailed in Jeopardy in 2011, Ken Jennings, who had won 74 games in a row before succumbing to Watson, famously borrowed a line from a Simpsons episode and wrote: I, for one, welcome our new computer overlords.

Kohn of IBM set the record straight right away.

Were not replacing anyone. Were not anybodys overlord, Kohn said.

Rather, in the world of health care, Watson aims to become the ultimate research partner and go-to idea catalyst for help with complex decisions.

When Watson prevailed in Jeopardy in 2011, Ken Jennings, who had won 74 games in a row before succumbing to Watson, famously borrowed a line from a Simpsons episode and wrote: I, for one, welcome our new computer overlords. IBMs Kohn says Watson doesnt want to be your doctor: Were not replacing anyone. Were not anybodys overlord.

In the new era of Big Data, Kohn notes that the good news is theres lots of information out there. The bad news is theres lots of information out there.

Information can be beautiful and helpful if you can find a way to access it, understand it and harness it.

Kohn, who was trained as both a biomedical engineer and a physician, says great engineers are skilled in critical thinking and learn where to find information.

In contrast, medical school seemed to be about how much rote information you could cram into (students) before they had a seizure.

The best med students and residents used to be the ones with the photographic memories or the hotshots who spent countless hours in the library memorizing the latest medical journals, then spouted off their knowledge during rounds.

But even the most amazing students and doctors cannot digest the amount of information that is now volleying toward us at an incomprehensibly fast clip.

Information doubles every five years, Kohn said. In 2010, the National Library of Medicine chronicled 699,000 new articlesIm sure you all would have loved to have read those 699,000 articles and use that information instantly any time you have to make a decision. You cant. But Watson can.

As health care gets more complex, the ultimate challenge says Kohn is to make wiser, more elegant decisions so patients get better care and all of us waste a lot less money on tests and treatments that dont work.

Enter Watson.

Artificial intelligence to the rescue

The reigning champion of artificial intelligence, Watson digests and speaks natural language, so it can respond to basic questions. And remarkably, Watson learns from its mistakes. During rehearsals for Jeopardy, Watson wasnt figuring out that in one category of questions, the right answers were all months of the year. After muffing three times, Watson heard the right answers from competitors and correctly guessed on the fourth try that the correct answer had to be a month. (Click here to see a documentary on NOVA, Smartest Machine on Earth, about Watsons creation and preparation for Jeopardy.)

One of the most advanced health care efforts underway is a partnership with Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York. (Click here to read more in the Atlantic.)

Kohn showed a demo of how Watson works with cancer doctors.

Imagine that an oncologist gets a new patient with metastatic lung cancer. That kind of cancer is incurable. So the doctors dilemma is to find the best treatment to help the patient live as long as possible with the best possible quality of life.

When the doctor first encounters the patient, Watson does a little research, browsing 3,500 medical textbooks, 150,000 relevant research articles, and of course, the patients entire medical record all in a matter of seconds.

This is the starting point, Kohn says.

Dr. Martin Kohn of IBM. Information doubles every five years. In 2010, the National Library of Medicine chronicled 699,000 new articlesIm sure you all would have loved to have read those 699,000 articles and use that information instantly any time you have to make a decision. You cant. But Watson can.

Watson then makes suggestions about possible courses of treatment, flags missing information and assists the doctor in making decisions.

If, for instance, the patient is a teacher of young children who does not want to lose her hair because that would spook her students, Watson can hunt for results from clinical trials on drugs that dont cause hair loss.

Watson is being taught that what patients want matters, Kohn said.

Watson also has the benefit of instant access to the newest information all over the Web. And since IBM has licenses with places like the New England Journal of Medicine, if an article was published online last night and you have to make a decision today, Watson will have already digested and factored in the relevance of that new study.

Watson is like a reverse search engine, Kohn says.

Type a query into Google and youll get a gazillion hits, starting with the ones that mostly closely matches your question.

Watson gives you the ideas first, then takes you back to the literature, Kohn said.

Along with Sloan-Kettering, IBM is working with WellPoint Inc., one of the largest health insurance companies in the U.S.

Nurses at WellPoint who determine the medical necessity of various treatments are training Watson so the machine can in turn help them make higher quality decisions on which therapies are most effective while also saving money.

It isnt perfect and it has to be taught, Kohn said. It doesnt say this is the answer. Im not making the decision for you. You use it or not use it as you wish. You are still the expert.

But some of the practical applications appear to be remarkably promising.

Watson, for instance, is helping monitor the most fragile of patients: premature babies in the neonatal intensive care unit at the Toronto Sick Kids Hospital. Those babies, of course, cant describe how theyre feeling or warn their caregivers of serious problems. But Watson can watch the babies movements and detect patterns before humans can see them. Watson monitors streaming data of physiological behavior. In addition to vital signs, Watson watches how the babies move. And their actions are providing remarkable information.

It can identify patients who will develop neonatal sepsis 24 hours before its clinically manifesting, Kohn said. As you know, in sepsis, even an hour earlier in intervening makes a big difference.

In another application, Watson has been able to predict which patients will develop congestive heart failure 18 months before they show any symptoms. If providers can access information like that, they can come up with care plans to prevent the disease from ever manifesting or doing harm to the patient.

Some physicians remain skeptical

Not everyone thinks Watsons future is perfectly bright.

One of the keynote speakers at Keystone, Dr. John Kenagy, worked as a physician during the early days of managed care, then learned what it was like to be a powerless patient when he broke his neck and had to spend six months immobilized.

Dr. John Kenagy: The key is to start with the patient. Watson is fascinating. But it needs to work not just at Sloan-Kettering but also in any small town in Colorado.

Kenagy later went to Harvards Kennedy School of Government and has studied how to use disruption as a tool for innovation.

Watson is very interesting and theres tremendous potential in exploring the role of technology in decision-supported care, Kenagy said.

He worries, however, that because pressure is so heavy to cut costs, some companies may want to use Watson in a way its creators did not intend: to make impersonal decisions driven by cost.

Kenagy is concerned too, about testing Watson in meccas of top-down traditional care like Sloan-Kettering. To Kenagy, that smacks of the old days during the industrial revolution when we viewed mechanistic solutions as saviors. Today the world is much more organic where solutions need to rise from the ground up.

The key is to start with the patient, Kenagy says. Watson is fascinating. But it needs to work not just at Sloan-Kettering but also in any small town in Colorado.

Technology is not a fix. Its an accelerator of what we know how to do, Kenagy said.

While Watson is partnering first with institutions, doctors and nurses, Kohn said the patient piece is absolutely critical.

If a patient is knowledgeable enough and empowered, youre more likely to come up with a plan that the patient will carry out, Kohn said. We have a vision for Watson in that role, not just something online, but as a part of integrated, patient-centered care.

Someday, at your doctors office, you might be able to meet with both your team of care providers and Watson to ask some pertinent questions about your symptoms and possible cures.

Globally, we want to make it easier to use that ocean of information that will help us make better decisions and overcome one of the obstacles to achieving transformation, Kohn said.

Tapping dear Watson to find what is elementary amid the chaos might sound a little crazy.

But that makes Kohn and his buddies at IBM quite comfortable. Kohn signs all his emails with a favorite quote from Albert Einstein:

For an idea that does not first seem insane, there is no hope.