By Katie Kerwin McCrimmon

The Affordable Care Act may leave many of the poor and people of color behind.

Thats the view of this years president of the American Public Health Association,Dr. Adewale Troutman, who spoke in Denver last week.

We are trying to incorporate 30 million people into a health care insurance system that is broken. The system is fragmented. Inequalities flourish and prevention is an afterthought, Troutman said during an event on health equity sponsored by The Colorado Trust.

The system doesnt necessarily change just because you have more people in it, he said.

While the Affordable Care Act, which goes into full effect next year, will help millions of people get health insurance, it does not guarantee that theyll get decent care. Nor does it go far enough to reverse disparities that cost lives every day, Troutman said.

For instance, health inequities cause more than 83,000 excess deaths among African Americans each year, Troutman said. He cited a study titled What if We Were Equal? that he and others did for the journal Health Affairs in 2005. When you add excess deaths among Latinos, Troutman said its as if a full load of more than 300 people the same number on the recent Asiana Airlines flight that crashed in San Francisco are dying every single day each year.

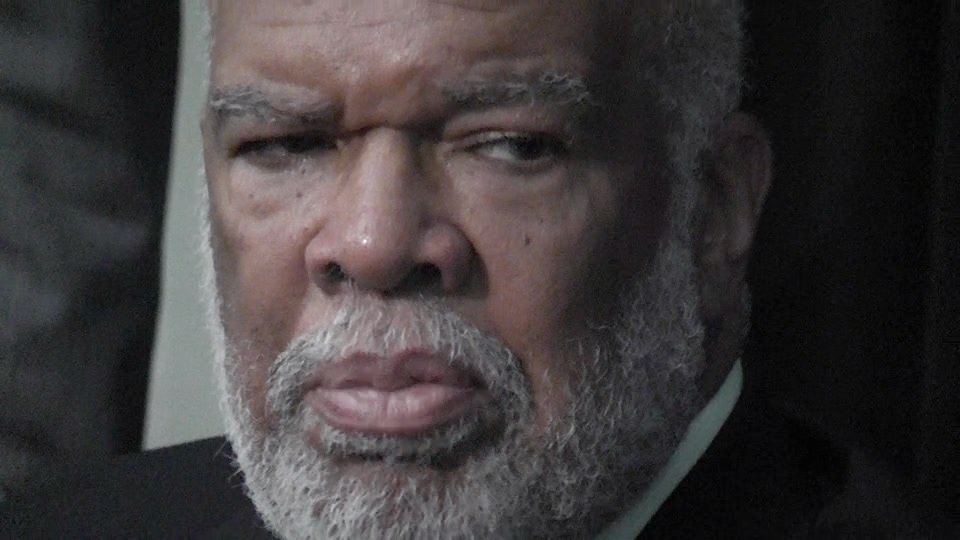

Dr. Ned Calonge, president and CEO of The Colorado Trust, which is sponsoring a series of sessions on health disparities.

Yet, he said few people seem concerned and the gap in excess deaths continues unabated.

The Colorado Trust is holding a series of events on health disparities in an effort to heighten awareness.

The Trust is changing its direction and its vision in addressing health equity, said Dr. Ned Calonge, president and CEO of the The Trust. Why now? We should all be fed up. We should all be working on this right now.

Calonge said policymakers must harness the power of the Affordable Care Act to build a movement toward health equity.

While Troutman estimates that health reform will help between 8 million and 30 million uninsured people gain coverage, having access to a doctor cant change unhealthy communities that disproportionately harm and kill the poor and people of color.

I do not support the Second Amendment. It has nothing to do with today. It was written in case the British came back. Dr. Adewale Troutman

For instance, Troutman said policymakers must examine the disastrous impacts of guns, especially as they affect young people like Trayvon Martin.

I do not support the Second Amendment. It has nothing to do with today. It was written in case the British came back, Troutman said, noting that his opposition to firearms is his own personal view and not that of the American Public Health Association, the largest association of public health professionals in the world.

I just dont see a need for the general population to have access to weapons, particularly weapons that can cause mass destruction, Troutman said.

He said that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recognized violence as a public health issue and that health workers should directly tackle gun violence.

Across the U.S. and the world, he said policymakers need to change their frame of reference when it comes to violence and health disparities. Its critical to recognize that we are all connected.

Its not us or them, its all of us, he said.

He quoted the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. who said that of all the injustices, injustices in health are the most shocking and inhumane.

Troutman cited disturbing health data from Colorado:

- Hispanic babies in Colorado are 63 percent more likely than Anglo babies to die in the first year of life.

- African American babies die as infants in Colorado at a rate three times that of white babies. That amounts to about 15 deaths for each 1,000 babies born a year.

- That infant mortality figure places Colorados overall rates between those of China and Colombia, according to health data from the World Bank.

- Infant mortality rates for Hispanics have climbed in recent years at the same time that mortality rates for white infants have steadily fallen, according to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

Among the bottom-line causes for health disparities are racism, income gaps, low-paying dead-end jobs and poor educational achievement.

Dr. Adewale Troutman, this years president of the American Public Health Association, said achieving health equity is a winnable battle. He urged public health workers to aggressively work to achieve equity.

Troutman said theres a direct link between poor educational achievement and all sorts of negative consequences. For instance, prison planners can anticipate the number of cells theyll need in the future based on the current number of dropouts.

On the flip side, people who do well in school get better jobs, have better health literacy, take better care of themselves and therefore have fewer behavioral health challenges.

Where do you spend your resources? If you spend more on primary education, you get more bang for the buck, Troutman said.

He joked that people who want better health outcomes should also make sure that life treats them well.

Dont be poor. Practice not losing your job and dont be illiterate.

Calonge said it can be overwhelming to tackle health disparities when they remain so difficult to reverse.

The sea is so big and my boat is so small, Calonge said, underscoring how vital it is to build partnerships with public health workers, community groups and nonprofits.

Denise Vazquez Troutman, who is married to Dr. Troutman and also works with him as president and CEO of the Center for Women and Families at The Troutman Group, said the key is making sure to fill the vast expanse of the sea with many motivated people.

If you look out in that sea and there are a lot of little boats, then creating health equity doesnt see quite so impossible.

Her husband echoed that optimism.

This is a winnable battle. I have to believe its winnable. Its going to take time and a different way of thinking, Troutman said. But there are many efforts moving ahead. I would love to see an increase in access to equitable care so we can close the gaps.