By Michael Lott Manier

In the wake of the heartbreaking tragedies in Aurora and Newtown, the debate over gun control has taken center stage in Colorado. The legislature is now set to consider an expansion of the ways in which individuals who have received treatment for mental health conditions or substance use disorders (collectively known as behavioral health) can be prohibited from purchasing or possessing firearms.

The rampage killings that reignited the gun control debate have been inextricably linked in the public consciousness with the issue of mental health. Politicians and gun-rights advocates have focused on the message that the way to keep our communities safe is to keep guns out of the hands of the mentally ill or the wrong people. Certainly there are commonsense ways to protect our communities from gun violence that focus on behavioral health. In fact, limiting access to guns among individuals who have been committed to a facility for mental health treatment is already part of Colorado law.

What the gun control debate in Colorado and across the U.S. has ignored, however, is that the most significant intersection of behavioral health and gun violence is not mass shootings nor violence against others. It is suicide.

Suicide, whether or not it is committed with a firearm, is an urgent public health issue in Colorado. In 2011 at least 910 Coloradans died from suicide, making it the seventh leading cause of death. Among Coloradans ages 10 to 34, suicide was the second leading cause of death more than homicide, influenza and pneumonia, diabetes, leukemia, lymphoma and heart disease combined. Only motor vehicle crashes kill more young people than suicide in Colorado.

One of the reasons for the consistently high suicide rate in Colorado is the use of firearms. Homicides by firearm have been trending downward in the United States thanks in large part to advances in emergency medicine. If someone is shot by another person during the commission of a crime in the U.S. and receives emergency care in time, he or she has about an 80 percent chance of survival. The chances are reversed when it comes to suicide. If someone uses a gun to kill him or herself, the fatality rate is 85 percent.

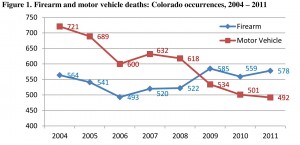

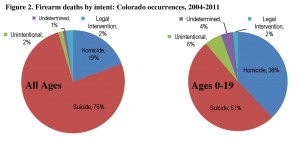

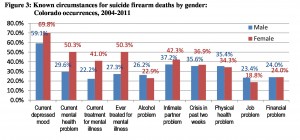

Nationally, two-thirds of all firearms deaths each year are suicides.In Colorado, the numbers are more acute. From 2004 to 2011, 4,362 people died as a result of firearm wounds in Colorado. More than three quarters of those deaths 3,315 were suicides. At least half of all suicides in Colorado are committed with a firearm. As is the case everywhere, the overwhelming majority of those killed are male. More white non-Hispanic men commit suicide with a firearm in Colorado than almost any other state.

These grim statistics stand in sharp contrast to the numbers associated with violence against others. People with a mental health diagnosis who do not have a co-occurring substance use disorder are no more likely than the general population to commit an act of violence against another person. Only 4 percent of violent crimes against others are committed by someone with a diagnosis of serious mental illness. The same risk factors that make someone without a diagnosable mental illness more likely to commit a violent crime also affect people with a mental health diagnosis and at almost exactly the same rates. The strongest predictors of violence against others are substance abuse, a history of trauma and low socioeconomic status. There is overwhelming evidence that managing those three risk factors greatly reduces violent crime. In contrast, there is no evidence showing that a lower rate of mental illness in a population is associated with a lower rate of violent crimes against others.

While the focus of politicians and gun-rights advocates may be on the danger posed to the public by people with mental illness, the most common intersection of violent crimes against others and behavioral health is actually the victimization of people with an untreated condition. Men and women with a serious mental illness who may or may not have a substance use problem are 11times more likely to be the victim of a violent crime than the general population.

Just as with other health conditions, social determinants of health employment, income, education strongly affect an individuals chances of having a serious behavioral health condition. People with an untreated behavioral health condition who are low-income and whose social supports are weak, are far more likely to be the victims of sexual assault, domestic violence and homicide than people who do not have an untreated condition. The trauma of those crimes also increases the victims risk of suicide.

As Coloradans continue to debate firearms, violence and behavioral health in our society, we need to remind everyone of the essential facts. We need commonsense gun violence prevention laws, but we also need to address the behavioral health needs of our most vulnerable citizens. Colorado is moving in the right direction as it restores some of the funding for behavioral health services that were cut dramatically during the recession, and we must advocate vigorously for each and every additional dollar.

Funding, however, is not enough. It is time to bring suicide in general, and especially the role of firearms in suicide, out of the closet and into the light of day. More than three-quarters of all firearm deaths in Colorado are suicides. These violent deaths are almost always the fatal symptom of an untreated behavioral health condition. When that is the case, they are 100 percent preventable. If saving the most lives is our top priority, if we want to rescue the most families from the tragedy of losing a loved one to gun violence, then our focus must include preventing suicide.

Michael Lott-Manier is the public policy and advocacy coordinator at Mental Health America of Colorado.