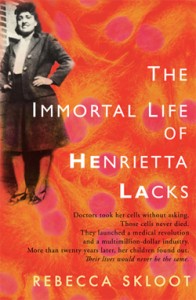

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, by Rebecca Skloot (Crown, 366 pages)

By Diane Carman

The first time that author Rebecca Skloot heard of Henrietta Lacks was in a biology class. Her teacher mentioned the name of the woman whose cells had been used in thousands of scientific experiments over decades, and had enabled scientists to discover breakthroughs in prevention of polio, gene mapping, chemotherapy, in vitro fertilization and advancements in the understanding of a vast array of medical conditions.

Skloots curiosity was piqued. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is the culmination of a decade of dogged reporting and relentless research to quench her thirst for information about the woman who had been abbreviated by scientists to mere clusters of cells and a label: HeLa.

Skloots work is meticulous. She has created a portrait not only of Lacks and her family, but of Henriettas physicians; the scientists who achieved what had until then been impossible by culturing the cells harvested from her cervix; and the lawyers, journalists, even clerical workers who encountered the dying young African-American womans biopsy tissue that ultimately would become a thriving global industry.

the scientists who achieved what had until then been impossible by culturing the cells harvested from her cervix; and the lawyers, journalists, even clerical workers who encountered the dying young African-American womans biopsy tissue that ultimately would become a thriving global industry.

HeLa has been exposed to nuclear radiation and launched into space. Rough estimates suggest that the tiny tissue sample has been cultured into more than 50 metric tons of cells, and that they have enabled scientists to advance medicine in incalculable ways.

Yet, few, if any, of the benefits of that research have been available to Lacks children and grandchildren due to their difficult lives and frequent periods in which they could not afford health care.

Their awareness of that fact and the resulting resentment is a central theme of the narrative as is the evolution of privacy laws and professional guidelines surrounding the use of human subjects in scientific research.

Skloot offers no simple answer to the question of whether human subjects should have control over the use of their tissues many of which are excised in medical treatments and would otherwise be disposed of routinely at medical facilities.

She does make it clear that the release of Henrietta Lacks name and medical records to the public no longer would be allowed under Health Insurance Portability and Privacy Act rules, but HIPPA offers no relief from the overwhelming sense of violation expressed by the Lacks family through the rampant objectification and commercialization of HeLa.

Immortal Life also chronicles the African-American experience with the health care system in the United States and the suspicion that often lingers among patients to this day.

Lacks was treated for her cancer at Johns Hopkins Hospital in the early 1950s when the institution was segregated to the point that even the morgue had a separate room for black bodies.

Rumors of grotesque human experimentation on blacks were rampant and discouraged African-Americans from seeking treatment. Given the documented cases of abuse of black patients around the country, including the Tuskegee syphilis experiment and others recounted by Skloot, mistrust of the medical establishment by African-Americans was understandably difficult to overcome.

The book is about medicine, science and history, but its also about the struggle of the members of one family caught in a culture they didnt understand and burdened by a loss so searing and personal that the generations that followed could never resolve their grief and confusion.

We didnt say words like cancer, one of Henriettas cousins told Skloot, and we dont tell stories on dead folks. It took the author years to engender their trust and to piece together the history of the familys struggles and heartaches that were occurring at the same time HeLa was transforming medicine and science.

Skloot weaves into the narrative her personal experiences as a reporter and frequent companion to Henriettas daughter, Deborah, conveying to readers the sense of triumph she felt when she finally persuaded a recalcitrant son to meet her or when she gained access to information long ago buried in aging memories, family lore and dusty, mildewed hospital files.

Skloots easygoing style and her tenacious reporting make Immortal Life an extraordinary work of narrative nonfiction and a thoughtful glimpse into the human beings hidden behind the walls erected in the name of science.